Teaching communication skills to our kids today means thinking twofold: traditional and digital. Raised among screens, apps, and the online world — including its communities and multitude of communication methods — means communication skills now firmly include:

- Asynchronous communication

- Text, email, and other digital notes

- Communication with fewer nonverbal cues

The way our kids communicate now isn’t just at the dinner table, the playground, and with the neighbors. It’s also happening in their digital world. As screens become a bigger part of how young kids play and learn, the question isn’t if screen time impacts communication skills, but how.

We’ve discussed this through the lens of digital social skills. Now let’s explore how communication and active listening skills develop in early childhood and how both screen-based and offline play can influence that development.

Nurture is a kids’ app that develops Life Readiness skills such as creativity, curiosity, and critical thinking. All the more important in the age of AI, they're developed through fun, interactive, story-driven adventures. Nurture Academy — that’s where you are right now! — is for parents learning what it takes to raise smart, happy, and resilient kids in our increasingly digital world. We’re glad you’re here!

Read on, then discover how Nurture works or get the app.

Why Communication and Active Listening Matter at Ages 4–7

Young kids are starting to expand their emotional vocabulary, experimenting with storytelling, and learning how to take turns in conversation. These skills are foundational for relationships, confidence, and learning.

Kids in this stage are transitioning from the biological cry — you know, the “I don’t feel good and I don’t know why” — to being able to say, “I’m frustrated,” or “I’m tired.” This is a critical point in a child’s development. They’re learning to express themselves with more clarity and emotional accuracy or, put another way, shifting from reactive behavior to reflective communication.

Let’s be really clear upfront: Spending time on screens is not inherently detracting from the development of these kinds of communication skills. In many cases, it’s actually helping them learn how to communicate by reinforcing traditional skills and fostering the development of new ones.

What we’re really seeing between ages 4 and 7 is the emergence of communication as a social tool, not just for getting needs met, but for:

- Building trust

- Showing empathy

- Navigating complex social moments

Whether it’s resolving a conflict in a game, telling a story to a friend, or even interpreting what a character on screen is feeling, kids are actively wiring the foundations of how they’ll relate to others for years to come.

This period also lines up with Erikson’s “initiative vs. guilt” stage — a phase where kids want to assert ideas, explore roles, and feel capable. Communication plays a huge role in that. The more we support their ability to express themselves and listen to others, the more confident and connected they become.

Listening is a core component of our ability to communicate. So-called expressive communication skills (verbal and nonverbal communication) and the receptive communication skills (listening) develop together. When kids feel heard, they learn to hear others.

When we model active listening, they begin to mirror it. And when they get the chance to practice — in conversation, in play, and yes, even during screen time — those skills take root and grow.

Play Is a Communication Power Tool

Play is one of the most natural, most powerful ways kids learn to express themselves. Maybe most importantly, it’s a safe space to work through thoughts, feelings, imaginings, and whatever else a kid might want to explore. Play can be a vehicle for experimenting with uncomfortable emotions, giving just enough psychological distance to fulfill that role more safely.

When a child says, “My character is angry,” it gives them space to express something they may not feel safe sharing as themselves. It lets them try out emotional language, observe how others respond, and even begin to problem-solve through social conflict, all without the fear of rejection or shame.

Whether they’re pretending to be a vet, taking turns in a board game, or navigating a tricky level in a digital co-op game, they’re developing communication skills in real time.

Pretend play, especially, creates space for storytelling and role-based conversation. Kids get to step into characters, invent dialogue, and try out different social roles. This all stretches their expressive language and imagination.

Practice with Verbal and Nonverbal Cues

In both physical and digital play, turn-taking, instruction-giving, and collaborative decision-making give kids repeated practice with verbal and nonverbal communication. They learn to listen, wait, explain, and adapt — all core elements of effective communication.

And yes, this absolutely applies to digital play. Well-designed games, when scaffolded or co-played with a caregiver, can amplify these benefits. Some games require constant coordination (“I’ll push this button while you move that block!”), while others encourage storytelling or emotional interpretation. When adults are part of the play, or even just nearby and engaged, those moments become even more powerful.

In other words, play is practice. It’s a communication skills rehearsal. It’s one of the most developmentally rich ways to build real-world communication skills.

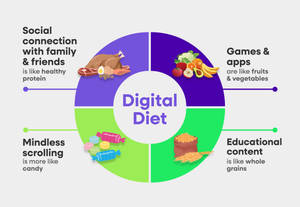

Not All Screen Time Is the Same

When thinking about the impact on communication skills, the type of media matters, but so does how it’s used. Passive viewing, especially when done alone, can be limiting in terms of language exchange and development. But interactive, shared, or reflective screen experiences can offer something meaningful: a space for dialogue, emotional labeling, storytelling, turn-taking, and other communication skills.

A video chat with a grandparent, for example, invites back-and-forth conversation. A co-op game may require players to communicate clearly and coordinate actions. Even a show can spark rich language development if it’s paused to reflect or watched alongside an engaged caregiver who adds context or asks questions.

Co-Engagement

This is where the role of the adult comes in. Screen time doesn’t automatically support communication skills, of course. It becomes valuable when caregivers scaffold the experience through questions, narration, emotional reflection, or simply staying present and involved.

One study found that toddlers who used touchscreens with a parent — who pointed out objects, labeled them, and described what was happening — learned new words more effectively than those who used the same screens alone. In other words, screens aren’t inherently educational. They’re tools. And the learning value depends on how we use them.

Another review emphasized the importance of contingent interaction, or the kind of responsive, back-and-forth dynamic that mirrors real-life conversation. When children engage in media experiences that invite repetition, labeling, and dialogue — especially with an adult alongside them — they tend to comprehend and retain language better than during passive viewing alone.

Active vs. Passive Screen Time

That distinction between active vs. passive screen time is an important one. Screen time that gets a child engaged, interacting, and making decisions within the experience can help them learn to communicate, and especially listen, such as for in-game clues or signals. But even passive media, like a quiet TV show, can become active when there’s co-viewing, reflection, or dialogue layered on top.

So instead of asking how much screen time is okay, a more useful question might be: Is this screen time opening the door to communication, even if my kids aren’t actually “talking” to anyone?

That simple shift can help caregivers use media more intentionally, without fear or guilt, and with more developmental impact.

How Caregivers Can Support Communication During Screen Time

Screens can easily become settings for rich, engaging communication and co-engagement, but it usually takes a little bit of adult presence and curation to unlock that potential. Remember to:

- Narrate

- Ask

- Label

- Co-engage

Here’s what I mean by that.

One of the easiest things to do is to narrate your own thoughts out loud. If you’re watching or playing alongside your child, verbalizing what you’re seeing, thinking, or feeling helps them tune in and make meaning. You might say,

- “That didn’t sit right with me — what do you think?”

- “Whoa, that surprised me. Did that surprise you too?”

This kind of reflective commentary helps kids learn how to process what’s happening on screen. It also models the idea that emotional reactions can be named, shared, and explored — not just felt and ignored.

You can also ask open-ended questions to invite back-and-forth dialogue:

- “Why do you think she said that?”

- “What would you have done instead?”

These kinds of questions keep the experience from being passive and instead encourage your child to explain, reflect, or imagine alternatives.

In moments where a show or game touches on a big feeling, pause and label the emotion together.

- “Hmm, they’re biting their lip — do you think they’re nervous?”

- “She acted happy, but her face didn’t match — what was she feeling?”

Noticing and naming emotions during screen time builds both emotional literacy and conversational awareness.

And finally, co-engagement (co-viewing or co-play) doesn’t have to mean constant conversation. Just being nearby, engaged, and occasionally asking questions or offering reactions helps kids feel safe and seen — and makes it more likely they’ll share their thoughts with you as they process what’s unfolding.

Active Listening Activities and Games — Offline and On-Screen

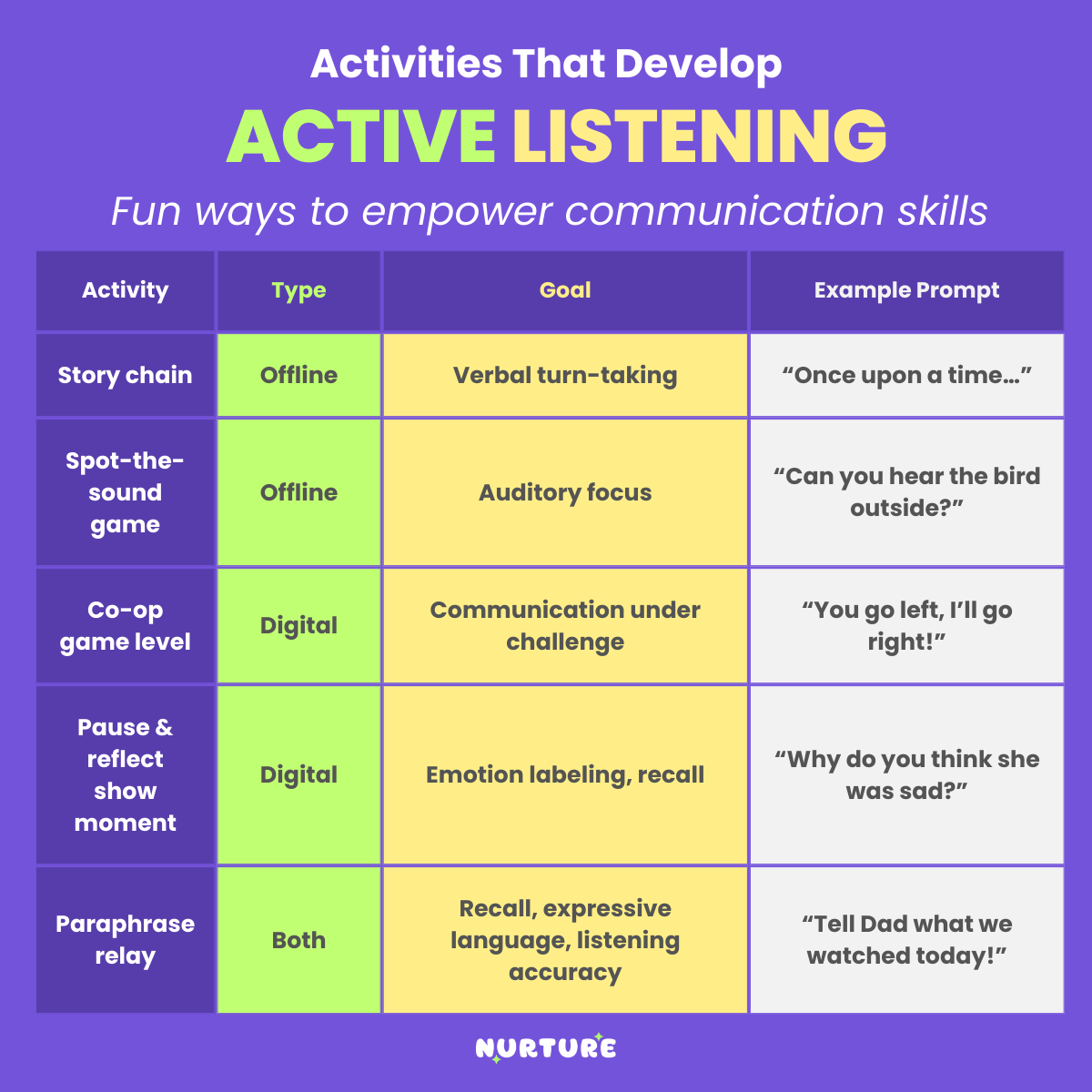

Everyday routines and play can double as active listening practice. Through fairly simple offline and digital games, we can practice focus, empathy, and verbal exchange with kids in fun, easy ways.

Here are some I’ve seen work especially well.

Aiming for Connection, Not Perfection

Communication skills don’t just happen during “teaching moments,” they’re built across the hundreds of little interactions kids have every day. Through conversation, play, storytelling, co-viewing, and reflection, they’re constantly picking up cues about how people listen, express themselves, and relate to one another.

When we bring intention into those moments, including during screen time, we help kids build confidence in how they express and listen.

But you don’t have to be intentional all the time. That’s just not realistic. The good news? Kids don’t only learn when we’re actively teaching. They learn by watching.

This is the power of observational learning. Children absorb communication patterns, emotional tone, and social habits by seeing them modeled. They can pick up cues from people beyond just their caregivers, but also from characters in games and shows, too. If the people on screen are listening, asking questions, or working through a conflict, kids are learning from that. They’re practicing through imitation, even if they’re not responding out loud.

We learn from watching other people do things. That’s why demonstrations are so effective. Even if you’re not able to co-play or co-watch every time, choosing media that models strong communication still matters.

So yes, be intentional when you can. Narrate your thoughts. Ask good questions. Label emotions. Co-play and co-view when life allows it.

But also remember: you’re modeling even when you’re not speaking. And kids are learning, even when it doesn’t look like it.

Find out more in the complete Parent’s Guide to Screen Time for Kids.

Copy Link

Copy Link

Share

to X

Share

to X

Share

to Facebook

Share

to Facebook

Share

to LinkedIn

Share

to LinkedIn

Share

on Email

Share

on Email