Counting, math, and basic economic concepts are taught in school, starting as young as pre-kindergarten, around 4 years old.

But real financial literacy? It’s not always on the academic curriculum, which means it falls into the Life Preparedness Gap. Life skills that kids need to grow into confident, happy, and healthy humans often come from other sources. Like other cognitive, social-emotional, and practical skills often stuck in the Gap, financial literacy can be a tricky one to teach kids.

Nurture is a kids’ app that develops Life Readiness skills such as creativity, curiosity, and critical thinking. All the more important in the age of AI, they're developed through fun, interactive, story-driven adventures. Nurture Academy — that’s where you are right now! — is for parents learning what it takes to raise smart, happy, and resilient kids in our increasingly digital world. We’re glad you’re here!

Read on, then discover how Nurture works or get the app.

That’s why we’ve compiled the collective knowledge of Nurture’s own Head of Learning, Musa Roshdy, and parenting educator/best-selling author Barbara Coloroso (kids are worth it!), and trusted research to answer the most common questions about financial literacy for kids.

Starting with…

Why Didn't Anyone Teach Me About Financial Literacy When I Was Growing Up?

This is the number one question I hear from parents when we talk about financial literacy. They know this is an essential life skill that could have potentially saved them a lot of hard earned learnings (and cash), and sometimes feel betrayed that no one taught them when they were younger.

Yet, when they think about setting their kids up for success, they acknowledge that it's often extremely difficult to teach children about financial literacy. Money is abstract, and adult systems are complex.

For young kids, money doesn’t yet hold the same emotional or functional meaning that it does for adults. They may see us swipe cards, tap phones, or talk about bills, but they don’t fully understand value, trade-offs, or future planning. They’re still learning impulse control. That’s developmentally appropriate: kids under 7 are still learning to delay gratification, understand time, and make consistent cause-and-effect connections.

Financial literacy involves emotional regulation (waiting, wanting, sharing), ethical thinking (fairness, honesty, generosity), and exposure to real-world decision-making. Without hands-on practice and guidance, kids often view money as either magical or off-limits. Money also takes a certain level of self-discipline that young kids are still developing.

Many adults struggle with financial skills themselves or feel uncomfortable talking about money. That silence, combined with cultural messages that promote spending over saving, makes financial literacy even harder to model and teach. Plus, it doesn’t help that most transactions now happen in completely digital environments, making the exchange of money an increasingly abstract concept for children to try and grasp.

As children deepen their understanding of the concepts of saving, spending, and sharing, they are also developing agency, self-regulation, and self-discipline that serve them well in other areas of their lives.

Foundations of Financial Literacy

Let’s start with some of the most common questions that get to the heart of the issue.

What is the right age to begin talking about money? How early is too early?

You can start as soon as your child shows interest, often around age 3, an age of intense curiosity, when they begin learning to count, sort, and compare. As long as they’re not still putting things (like coins) in their mouths, it can be beneficial to introduce simple financial concepts.

Let kids get familiar with bills and coins, and even with making small financial decisions. This age is for exposure and conversation. An in-depth understanding can come later.

How do I model healthy money habits with my child?

What we do, especially in front of our kids, matters even more than what we say to them. You can model everyday financial things like making budgetary decisions, talking about needs versus wants, or explaining why you give to a certain cause or community organization. Consistency, honesty, and transparency build trust and learning.

What words can we use (or not use) when discussing money so it’s developmentally appropriate?

Avoid complex financial jargon. Just use real-life terms like “saving for later” or “spending on snacks.” You want kids to understand money in real terms, so discuss it in the same way. Simplify something like a mortgage or a credit card, but most other approachable terms will land. Kids will likely walk you through any questions they have or words they don’t understand, helping you match their pace of learning.

Budgeting & Earning

Start exposing kids to the most important financial topics — making money and deciding how you’ll spend it.

How can I help my child create their first mini-budget?

Let kids manage a small amount of money regularly, such as weekly or monthly. Help them sort it into “save,” “spend,” and “share” containers or envelopes. Encourages child-led budgeting with light-touch parental guidance, so they learn by doing.

Should I give my kid(s) an allowance? At what age?

Even kids as young as four can be empowered by begining to explore money matters. As soon as you want to start teaching your kids about money and they understand some of the basics, giving kids an allowance — not as something to earn, but as a learning experience in money management — is recommended.

This gives them safe opportunities to make decisions with money, like saving, spending, sharing, and occasionally making mistakes. Better they learn now than when they have their first credit card.

Should chores be paid? What types of work should come with an allowance?

The conventional wisdom on chores has changed since we grew up. Giving children a standing allowance to teach money lessons is recommended. Paying kids for good grades and helping with basic household duties is not.

Age-appropriate chores are just a fact of life, and part of their responsibility as family members. If you create the expectation that they should be rewarded for being helpful around the house, children actually become less likely to contribute unless they are being compensated.

Paying for chores gives kids the impression that they’ll have to be rewarded or compensated for covering their basic responsibilities. These false expectations can make them less likely to practice helpfulness and take responsibility. However, offering small payments for “above-and-beyond” tasks can teach work-reward connections.

How should I explain why parents go to work?

Position work as part of caring for each other and contributing to the community. You can explain that parents do many kinds of work to help their family and others — some of it is paid, like jobs, and some of it isn’t, like cooking meals, cleaning, or comforting a friend. This helps children see that all kinds of work matter, not just the ones people get money for.

Keep it simple and concrete. You might say, “I work because I like helping people solve problems” or “Mama’s job lets her care for other families too.” Pair these with examples of the important work you do at home: “And when I cook for us or listen to your stories, that’s also work that keeps our family strong.”

Model the values you want to pass on. Share what you enjoy about your work — connecting with people, solving problems, creating new things, or helping others. You can also name when work feels hard, so kids understand it’s normal to have mixed feelings.

Show them you value rest and relationships as much as work. Subtle reminders like “After work, I can’t wait to read your bedtime story.” This helps them feel how much you value your time together and shows that caring for each other is just as important as the work you do.

Saving, Spending, and Sharing

These are the core concepts of doing things with money. How can we practice, balance, and model them?

How do we decide what portion of money goes to saving, spending, and sharing?

You might start with your own save/spend/share balances, or you may want to improve or simplify them.

You can also start by asking your kids what they think would make sense. Talking through those responses can be more valuable than how much money ends up where, at least for now. Taking a flexible approach and helping them understand why that’s important will also make the learning experience more realistic and beneficial.

How do I help my child set and work toward their own savings goals?

Help your child pick a goal — like a new experience, book, or toy — and figure out how many “allowances” or weeks of saving it might take. Use real goals so the impact is most meaningful. Use this also as an opportunity to think about their balance of spending, saving, and sharing in relation to how long they can or want to wait for that goal.

What are meaningful ways to encourage generosity (and not guilt)?

Model and talk about the ways you share with others in your everyday life. Invite kids to notice when someone in your family, neighborhood, or community could use a hand, and brainstorm together how you might help. This could mean sharing toys with a friend, making a meal for a neighbor, or helping clean up a local park.

Encourage them to see generosity as part of being connected to others — we all give and receive help at different times. Avoid guilt or pressure, so they learn that true generosity grows from care and relationships, not obligation.

Real-World and Experiential Learning

What kind of everyday, play-based, and digital tools help teach financial literacy?

How do budgeting games and simulations benefit financial literacy?

A play-based approach to learning financial concepts at a young age offers kids a safe sandbox for decisions and mistakes. Kids can experiment with spending, saving, and giving in a low-stakes context, learning cause-and-effect through play. When kids play, they become more deeply engaged and persistent.

They can learn the emotional investments of money as the financial happenings impact their pretend worlds. These repeated, enjoyable moments of practice help solidify skills and encourage creative problem-solving, not just memorization. These experiences should be accompanied by conversations, not just guidance, to encourage reflection and real-world thinking.

Can apps or online tools help teach financial literacy? Which are best for younger kids, ages 4–7?

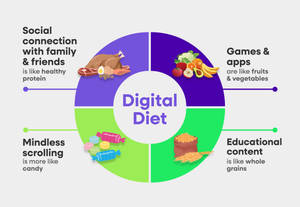

Yes — when used with purpose and guidance, digital tools can support financial learning in young children. Apps that encourage kids to sort money into categories, save toward a goal, or role-play spending decisions can help build early money habits through repetition and reflection.

Dr. Rachel Kowert, a Nurture parenting expert and award-winning research psychologist, clarifies that not all screens are created equal. Screen-based learning works best when it’s interactive, age-appropriate, and co-engaged, meaning a caregiver is nearby to support or reflect on what’s happening in the game.

The key isn’t the screen itself, but how it’s used. When apps are thoughtfully chosen and supported by adult involvement, they can be powerful tools for exploring real-world skills, including how we manage money.

One type of digital money should be avoided, though: loot boxes. This in-game element, along with similar financial mechanics, helps children become accustomed to spending in-game currency or their own money (or their parents’ money) on random prizes. These elements share similarities with the foundations of adult gambling addiction. Games should model how to build healthy habits with money, rather than encouraging risky spending behaviors.

What kind of real-world and role-playing games can enhance financial literacy?

The best money lessons often start with pretend play. For young kids, hands-on experiences are more effective than lectures. Games that mimic real life can help build foundational skills like saving, spending, and sharing.

Here are a few playful, off-screen ways to bring financial literacy into everyday life you can try and customize to suit your family’s goals, progress, and values:

- Play store or restaurant: Set up a mini shop with toys or snacks, and take turns being the customer and cashier. Use play money to practice paying, giving change, and making choices within a “budget.”

- Sort and save: Use labeled jars or envelopes for “save,” “spend,” and “share.” Give your child coins or tokens to sort after small tasks or pretend jobs. Be sure to talk through their decisions.

- Money goal chart: Pick a small goal (like a toy or outing) and track savings with a visual chart, so kids can color in sections as they save, reinforcing delayed gratification and self-discipline.

These kinds of games help kids build confidence with money in a low-stakes, developmentally appropriate way. They also open the door for meaningful conversations about value, choices, and generosity while keeping learning playful.

The Value of Money Mistakes

Learning is most impressed when it involves trying, then experiencing the impact of your decisions. Kids need a safe space to make mistakes to build financial literacy.

What should I do when my child overspends or makes a “money mistake”?

Let them make the mistake (within reason) — and then talk it through together. Keep the experience dignified, not shameful or punishing, and emphasize the learning experience. Help them appropriately understand the consequences and their part in sharing them. Ask them what happened, what they might do next time, and how they think it could be rectified.

How much freedom vs. limits do they need to learn from errors?

Parents can give as much responsibility as a child can handle, with a light structure. For example, letting them spend from their “spend” jar while keeping savings off-limits. The accompanying discussion can help them understand the impact of temptation to dip into savings and the frustration of having to wait longer for what they’re saving toward.

Values, Media, and Ethics

Money gets complex quickly, so how can we prepare kids to understand and overcome the money challenges ahead and the sources they trust?

How do we teach kids about needs vs. wants in an advertising-driven world?

Use real examples: snacks vs. groceries, toys vs. school supplies. You can also break down the value, expense, or unit price to explain to them why something may not be a smart financial decision. They’ll also learn through their own small money mistakes, which help them realize the impact and emotion of needs and wants.

My child asks for everything — they want it now. How can I help them delay gratification?

This is a totally normal part of development. Young kids are still learning how to manage big feelings and wait for what they want. But you can help them build the skills of delaying gratification and patience over time.

Simple routines can limit impulsive decisions. For instance, not bringing “their” spending money to the store unless there’s a plan. You can also set shared goals (“Let’s save for that together”) or create a visual tracker so they can see their progress toward something they want.

Learning to wait, control impulses, and delay gratification can be tough, but with consistency, encouragement, and celebrating every small win along the way, kids can start to feel proud of their ability to save, pause, value, and choose.

What should I do when my child lies about money (like sneaking coins or hiding spending)?

Model honesty for yourself. When money mistakes happen, like overspending or impulse buys, treat them as opportunities for growth, not guilt. Children learn ethical behavior through example and empathy, not shame. Help your child take responsibility with dignity. Ask open-ended questions to encourage reflection and accountability, not defensiveness.

Should we introduce debt and borrowing concepts to young kids?

Yes — in simple, age-appropriate ways. You could set up a family savings and loan bank, where kids can borrow a small amount of money and pay it back over time. Want a new bike instead of a modestly priced used one? They can borrow the difference and learn what it means to pay it back. This builds trust, helps them understand the idea of borrowing, and introduces repayment in a safe, supported way.

How do I explain the idea of credit to a young child?

Start with real-life experiences. Explain how you used a credit card for an emergency expense, got a loan for a car, or borrowed for a mortgage. You can explain that credit is essentially a promise to pay later and that it requires honesty and trust. Kids learn best when they experience these dynamics in small, manageable ways.

For young kids, going up to the “spend, save, and share” level of complexity is plenty. They can take on the deeper concepts as their academic math skills advance, too.

When is the right age to introduce investing? What should they understand first?

At ages 4–7, investing is generally too abstract. Focus first on habits like saving consistently and setting goals. If your child is curious, you can introduce the idea that some money can be “put to work” to grow slowly over time, like planting a seed and waiting for it to grow. Keep it conceptual, not technical.

Bigger Money Moments and Financial Well-Being

What about when money is a big deal in the family at the moment, or we want to instill bright aspirations?

How can I connect money conversations to my child’s bigger goals, interests, or dreams?

Talk to your child about how money helps us take care of ourselves, help others, and plan for fun things we want to do. Whether it’s saving for a trip to the zoo or donating to a local shelter, money becomes more meaningful when it’s tied to something personal. Parents can bring kids into real family conversations about planning and purpose. This can also help them understand the value of delayed gratification and work itself.

Can financial lessons help my child become more empathetic or community-minded?

Generosity and empathy grow when kids see how their choices can support and connect them to others. Sharing resources, when rooted in care and community, helps children feel their part in something bigger than themselves.

Invite your child to help decide how to share — whether it’s pooling allowance for a neighborhood project, buying groceries for a family friend, or finding creative ways to support someone nearby. These conversations shift money from being just about “me” to something that helps nurture relationships and strengthen the whole community.

How do I talk about big financial decisions without overwhelming my child?

You don’t need to explain everything, just enough to help your child feel included and secure. For example, if you’re saving for something big or making changes to your budget, you can say, “We’re making choices right now to help our family in the long run.” Keep the tone confident and calm. Be honest without burdening kids. Invite their curiosity, and reassure them with stability.

How to Teach Money to Kids

Financial literacy doesn’t need to be overwhelming, nor do you need to wait for kids to be much older than 3 or 4 to get started. With simple language, daily routines, and playful practice, even young kids can start learning how money works and how to make thoughtful choices.

Ready to go deeper? Explore our full guide on how to teach financial literacy to kids (ages 4–7) for activities, expert advice, and research-backed strategies.

Copy Link

Copy Link

Share

to X

Share

to X

Share

to Facebook

Share

to Facebook

Share

to LinkedIn

Share

to LinkedIn

Share

on Email

Share

on Email