Many adults are doing well by conventional measures. They have careers, responsibilities, and routines that function. Yet when asked to reflect on what actually made adulthood feel manageable emotionally, socially, and personally, a different picture often emerges.

To better understand which life skills matter most over time, Nurture’s co-founders invited professionals across industries to reflect on a single question:

Which life skills do you wish you had learned as a child to navigate your career and life in healthier ways?

We received responses from more than 50 individuals with varied backgrounds and roles. While their experiences differed, their reflections consistently pointed to the same kinds of skills. And they were not technical knowledge or academic preparation, but foundational abilities related to emotion, communication, and self-regulation.

These responses offer a useful lens for understanding why early childhood life skills matter and how they shape long-term wellbeing.

Nurture is a kids’ app that develops Life Readiness skills such as creativity, curiosity, and critical thinking. All the more important in the age of AI, they're developed through fun, interactive, story-driven adventures. Nurture Academy — that’s where you are right now! — is for parents learning what it takes to raise smart, happy, and resilient kids in our increasingly digital world. We’re glad you’re here!

Read on, then discover how Nurture works or get the app.

What Adults Say They Were Missing

Because the question focused on life skills, responses rarely mentioned subject matter or professional training. Instead, people described abilities that influence how they handle challenge, uncertainty, and relationships.

Common themes included:

- Managing failure without becoming discouraged

- Speaking up and expressing needs

- Asking for help without feeling inadequate

- Regulating emotions during stress

- Setting personal boundaries

Many respondents noted that they developed these skills only later in life, often after extended periods of stress or difficulty. In other words, these were not skills people consciously recognized as missing, until adulthood required them.

The Impact of Learning These Skills Later

Several responses described not just the absence of a skill, but the consequences of learning it later than necessary.

People reflected on experiences such as:

- Chronic stress or burnout

- Difficulty separating self-worth from performance

- Avoidance of conflict or self-advocacy

- Overwork driven by fear rather than intention

One respondent shared that they tied their self-worth closely to productivity, leading to early burnout. Another described learning to set boundaries only later in life, after years of stress.

The impact of learning these skills late was not primarily about professional advancement. It was about personal health, emotional stability, and quality of life.

A Common Thread: Permission

When we reviewed the responses collectively, a deeper theme emerged. Many adults were not simply wishing they had learned specific skills, such as confidence or emotional regulation. They were describing something more foundational:

A lack of permission.Permission to:

- Ask questions

- Seek support

- Set limits

- Rest

- Acknowledge uncertainty

This sense of permission — or lack of it — shapes how people approach learning, relationships, and challenges throughout life. Importantly, it does not suddenly appear in adulthood. It develops gradually, through early experiences and interactions.

Why These Skills Are Foundational, Not “Soft”

Skills such as emotional regulation, adaptability, communication, and empathy are sometimes described as “soft skills.” The reflections in this report suggest otherwise.

These abilities are central to how people function — in work, relationships, and personal decision-making. They support:

- Problem-solving under pressure

- Collaboration and perspective-taking

- Recovery from mistakes

- Long-term resilience

They also remain uniquely human. While technology may change how tasks are completed, it does not replace the need for judgment, emotional awareness, or social understanding.

Why Early Childhood Matters

From a developmental perspective, it is not surprising that adults reflect on learning these skills later in life. Early childhood — particularly between ages 4 and 7 — is a critical period for developing:

- Emotional awareness and regulation

- Flexible thinking and problem-solving

- Confidence after mistakes

- Social understanding and cooperation

- A sense of autonomy and safety

These skills are not taught through formal lessons. They develop through everyday experiences: play, conversation, trial and error, and supportive relationships with caregivers.

What “Life Skills” Look Like for Kids

Supporting life skills in childhood is not about accelerating kids toward adult outcomes. It is about helping them build the capacity to navigate everyday challenges.

For young children, this means learning:

- How to handle frustration

- How to recover from mistakes

- How to ask for help

- How to persist without becoming overwhelmed (resilience)

- How to understand their own emotions and those of others

These experiences lay the groundwork for the skills adults later recognize as essential.

What This Means for Parents and Caregivers

One reassuring takeaway from these reflections is that life skills do not require formal instruction to develop. They grow through:

Supportive responses to mistakes

Opportunities to try, fail, and try again

Clear emotional language

Respect for boundaries and rest

Modeling curiosity and self-regulation

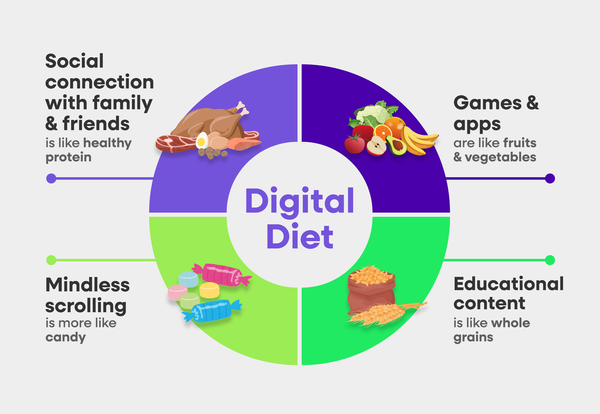

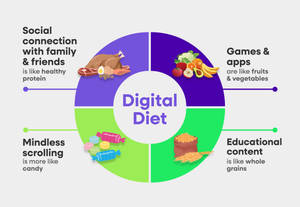

Digital tools and games can also support these skills when chosen thoughtfully and used with intention — particularly when they encourage active engagement rather than passive consumption.

Learning From Adult Reflection

When adults look back, they often realize they did not need more information as children. They needed more support in learning how to manage emotions, ask for help, and navigate uncertainty. These reflections are not about regret or blame. They offer perspective.

By understanding what adults wish they had learned earlier, we gain insight into how to better support children today — not by pushing them forward, but by helping them develop skills that support wellbeing across a lifetime. Especially as AI leans into many of the tedious, process-driven skills and human-centric creativity, flexibility, empathy, and ingenuity increase in value.

At Nurture, we believe life skills are not secondary to learning. They are foundational. When supported early, they help children grow with confidence, resilience, and care, both now and in the years ahead.

Copy Link

Copy Link

Share

to X

Share

to X

Share

to Facebook

Share

to Facebook

Share

to LinkedIn

Share

to LinkedIn

Share

on Email

Share

on Email